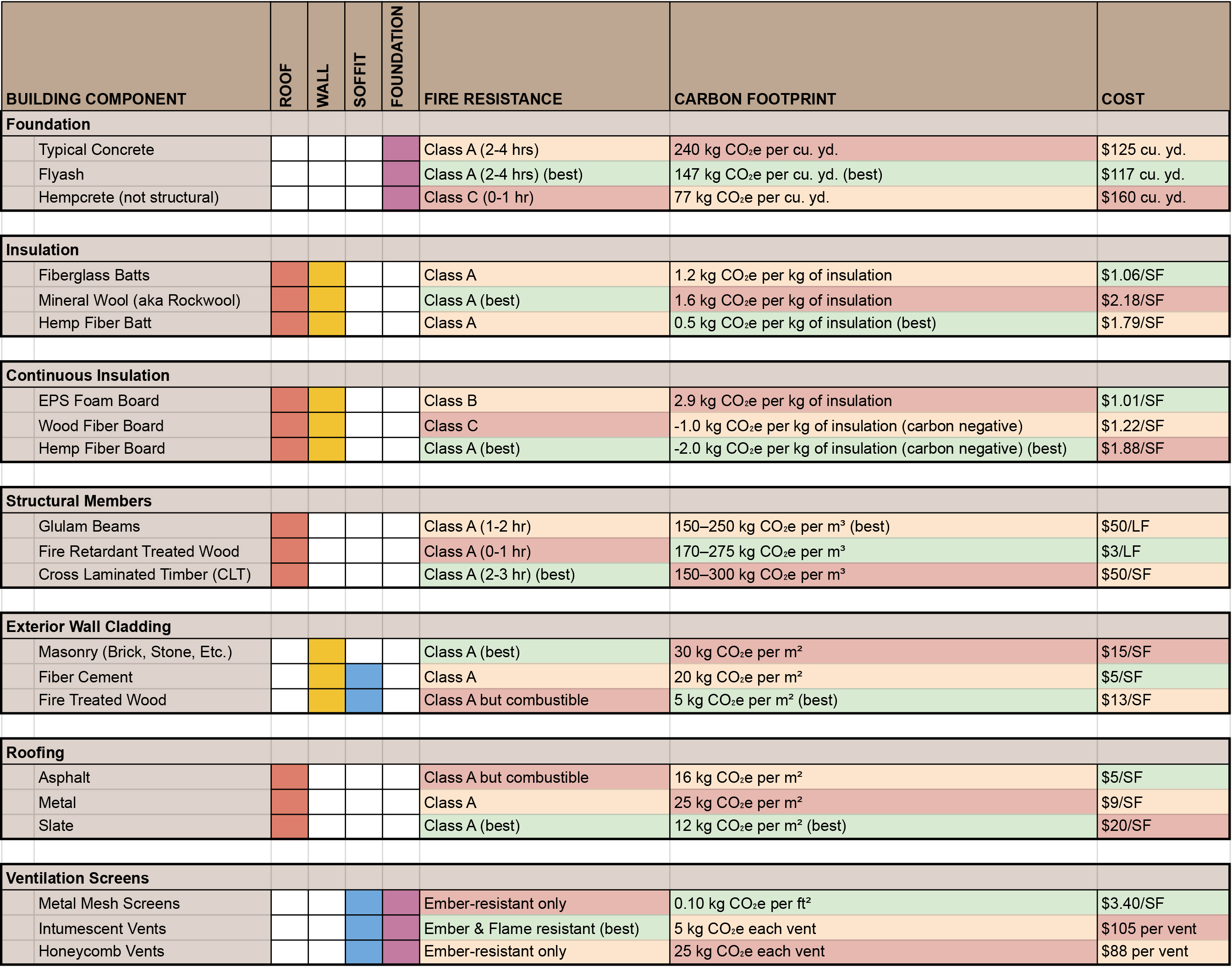

A model and matrix showing fire resilient materials and their application.

Wildfires are no longer distant, seasonal events—they’re reshaping how we live and build in the Northwest. As residential architects based in the Methow Valley, we’ve seen firsthand how urgent and disruptive fire can be. For us, designing with fire in mind isn’t optional—it’s essential. But it’s also something that communities beyond high-risk zones need to start considering.

The Wildland–Urban Interface is where vegetated areas meet developed areas—exactly the place where wildfire risk and human impact overlap. Washington’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and the U.S. Forest Service map both WUI zones and statewide fire risks. If you’re in a WUI and a high-risk area, Washington building codes already require fire-resilient materials.

Architecture always involves trade-offs. When we design, we’re constantly balancing four priorities:

We use a matrix to visualize different materials—like siding, roofing, or insulation—against these categories. The goal is clarity: what matters most for this project, in this place, for these people?

Exterior cladding is one of the first lines of defense. Fire codes encourage “Class A” materials—those with low flame spread ratings. Some materials, like masonry, fiber cement, or certain fire-treated woods, are also considered non-combustible.

Roofing materials face the same scrutiny. While asphalt shingles, metal, and slate all meet Class A requirements, only metal and slate are truly non-combustible. But even here, it’s complicated: metal offers great fire resistance, yet carries a higher carbon footprint and cost compared to asphalt.

We won’t sugarcoat it: the best fire-resilient, low-carbon materials don’t always win. Budgets are powerful drivers in the construction process. In many of our projects, the final material mix ends up being part fire-conscious, part carbon-conscious, and part cost-conscious. It’s a balancing act that reflects the reality of building today.

The takeaway? Fire resilience isn’t just a Methow Valley concern—it’s part of a growing reality across Washington. Good design can’t prevent wildfire, but it can shape how our homes and communities withstand it. By balancing cost, carbon, and beauty with fire safety, we’re able to design homes that are not only durable and sustainable, but also inspiring places to live.

Interested in exploring how fire-resilient strategies could shape your next project? Reach out—we’d love to help you think through your options.